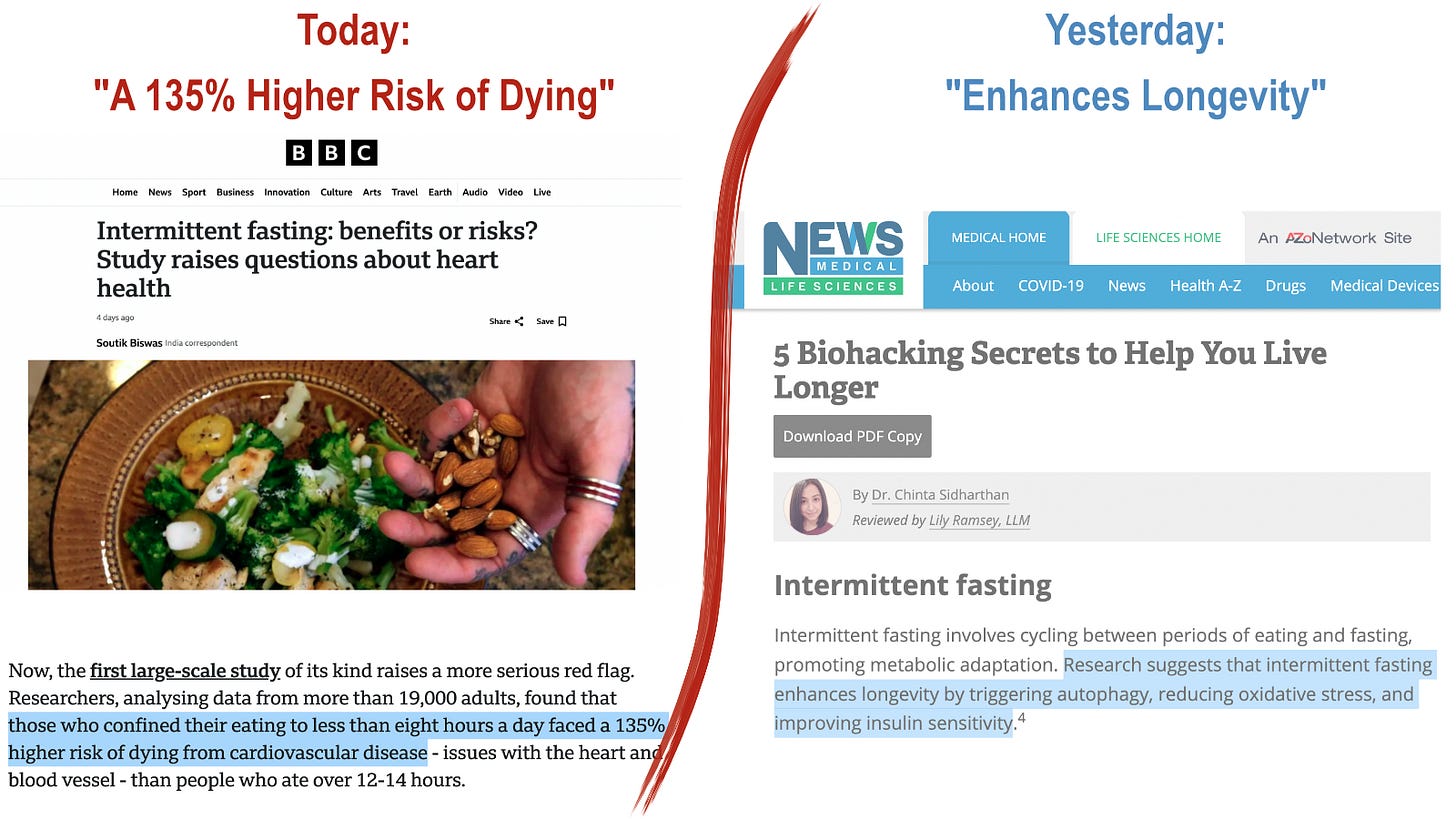

The BBC's Take on Intermittent Fasting: A Bad Diet or Bad Reporting?

A Warm-up to My Medium Day Presentation: From Confused to Confident.

TL:DR? Listen to the podcast here

What is New?

A widely reported observational study linked intermittent fasting (eating in an <8-hour window) to a 135% higher risk of cardiovascular death, challenging years of research that suggested the opposite: substantial health and longevity benefits.

Why It Matters

The more confusion there is from sensational headlines, the more urgent it becomes for readers to develop critical skills to distinguish between a real health threat and statistically flawed reporting. This post is about teaching this skill.

Your Takeaways

A practical illustration and guide of how to verify the media’s health news about observational studies.

A thorough understanding of the nine Bradford Hill criteria to which every claim for causation has to stand up.

A surprisingly simple metric for kicking the tires of observational studies.

Free download: a 5-minute clinician briefing and a patient handout. They’ll help you alleviate your patients’ concerns about the media’s U-turn on intermittent fasting. BONUS - The Causality Cheat Sheet: A powerful tool born from this analysis. This one-page checklist, based on the Bradford Hill criteria, will equip you to critically evaluate any health news you read in the future.

Table of Contents:

A Whiplash-Inducing Headline and the Real Story

The Study in a Nutshell: What They Did and What They Claimed to Find

How the Study Was Done

What the Study Found

The First Filter: Is It a Real Cause or Just a Coincidence?

The Second Filter: Are the Numbers Even Reliable?

The implausible effect on all-cause mortality

The More Likely Explanation

The Real Story and Your Path Forward

Downloads

A Whiplash-Inducing Headline and the Real Story

It is one of those whiplash-inducing media darlings which say, in essence, ‘forget our yesterday’s health gospel, it actually is a vice (at least until tomorrow when we’ll send you on another wild-goose chase, …and laugh our heads off in the newsroom)’.

Thanks to the media’s past health news, you have habituated intermittent fasting (IF) in expectation of the promised health and longevity dividends.

Celebrities (always a reliable medical resource) have endorsed IF, from Jennifer Aniston and Hugh Jackman (16:8 routine) to Jack Dorsey (OMAD, one meal a day).

And now…this: a 135% higher risk of dying from a heart attack.

Why, for crying out loud, can’t they make up their minds? The answer might surprise you: “Because of you”. As long as you reward sensationalizing headlines and their carefully crafted effects of fear and confusion with clicks and reads, you won’t get accurate information.

So, before you throw away a promising health strategy because of one headline, even if it’s from the BBC, let’s do what they should have done: scrutinize the evidence like a scientist would, and ask the hard questions.

You’ll be surprised to learn that you don’t need to be a scientist to accomplish that.

You’ll walk away with a 9-point cheat sheet for your own blow-by-blow scrutiny of future health articles. And, of course, with the ability to confidently decide whether you should be more worried about intermittent fasting or the state of science journalism.

Think of this post as a warm-up to my upcoming presentation on Medium Day “From Confusion to Confidence”. You’ll find the registration link at the end of this post.

Before we dive into the critique, let’s first do the blindingly obvious: look at how the researchers conducted their study and what the headline-grabbing results really were.

The Study in a Nutshell: What They Did and What They Claimed to Find

The study wasn’t a new experiment. It was a secondary analysis of data from the U.S. NHANES health survey [1]. “Secondary analysis” is an academic euphemism for “let’s see what associations we can find in data that weren’t collected to find those associations in the first place”.